Simon's Portfolio

Projects

A Suspended Solution

My senior year FSAE competition ended anticlimactically. Our car failed 3 laps into endurance after our lower control arm buckled, leading to a failed steering rack, and an undriveable car. The puzzling part: there’s a bend right in the middle of the lower aft link. The car was rounding a slow corner, maybe 0.3-0.5 g of lateral acceleration. We were all stumped. I got another crack at the problem after graduating, unfortunately too late to finish endurance, but I can finally sleep at night.

Lo and behold, the car that gets built after the pandemic, which continued to use our suspension geometry, breaks their lower control arm. I get this picture in March of 2022:

Apparently we passed on a bit too much of the torch

Apparently we passed on a bit too much of the torch

That looked eerily familiar. My nemesis had returned. Along with some other alumni, we brainstormed with the team to try to dig into what went wrong. I started by digging into how they designed the suspension links: what forces were they expecting, and how did they predict them. The low hanging fruit would be undersized links causing an expected failure. They were using the same force-moment method calculations we were in 2019, a discovery I should have seen coming. This meant we missed something my year, so I felt some level of responsibility. The Matlab script said it should work, and the buckling load calculations showed a factor of safety I felt comfortable with.

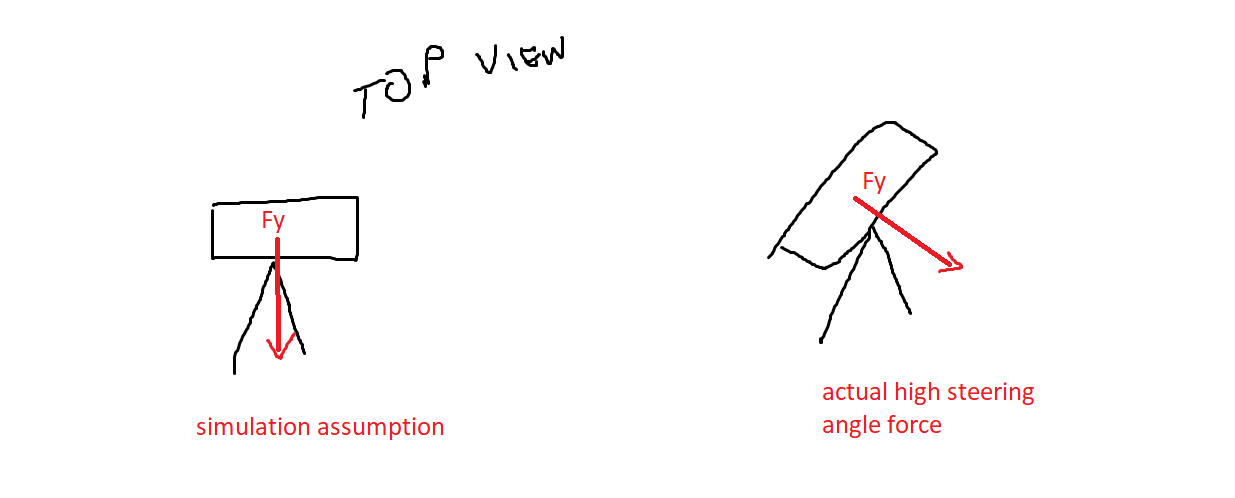

The calculations we ran in 2019 modeled the maximum lateral acceleration we could achieve. However, they simplified one key aspect: the wheel turn was negligible. After all, the same acceleration can be achieved at an arbitrarily high radius of curvature, so we can ignore it… right? Except we weren’t seeing failure at max ay. From a video I was sent of the recent failure, I did some back of the napkin math: width of a parking space 2.5m, the car took 8-10 frames to cross parking space, 30 frames per sec = ~8-9 m/s, skid pad radius ~20m gives ay of ~4m/s or 0.5g which makes sense for Cooper Union.

This meant our model was ignoring something really big, big enough to break the car 2 years running. The failure on both occured at low speed, near full lock. Steer angle was not represented in our model. That proved to be our bugbear.

Jimmy Neutron would have called this a “brain blast”

Jimmy Neutron would have called this a “brain blast”

To fix the calculations, the input force matrix needed to be rotated to align with the steer angle. In Matlab, this is a simple rotz command. In the python script they were developing, it required a little more linear algebra. I recieved news that at full lock, the new simulations did indeed show the forces far exceeding the bending yield stress of the link. Armed with this new knowledge, the team set off to conquer the new car.