Simon's Portfolio

Projects

Preface

There is nothing to disparage previous powertrain leads about the design, and I was only allowed to take such a critical look at their work because I was standing on their shoulders. Nothing below should be taken as derisive, derogatory, or dismissive to the people whose mantle I was taking on. Any issue with the work that was done by them or in their name is part of the process we call engineering, and I have no shame about the mistakes in the work produced under my leadership for the same reason, despite the guarantee that a younger student is shaking their head about my poor decision about some aspect of the car.

2019 FSAE Competition

To ensure we were rigorous in our engineering design cycle, we have to identify the problem. Our problem? Well, in 2018, we didn’t finish the competition, so our points scoring ability was greatly diminished. To ensure our points scoring ability is absolutely maximized, we have to finish every race. This means we have our car has to start when asked, and keep going until asked to stop.

Reliability is one of those design goals that is really hard to quantify. It’s only ever truly assessed after the race, meaning its too vague of a goal to use to design. The way reliability is designed for is to run someting until it breaks, look at what breaks and fix it. This can be very hard if your budget is small. We were not in the position to run the engine until it broke. WHat we could do is run the engine as often as possible. With some good engineering judgment, low hanging fruit can be picked up and solved.

Low Hanging Fruit 1: Throttle

Our team had a history of inconsistent throttle performance. Even glancing at the throttle body could send an engineer into convulsions, so the picture below will be pixelated so I will not be liable for your hospital bill

This throttle body had been in use since before 2016, but it looks like it was built on Dr. Frankenstein’s workbench right next to his monster. It was an aluminum lip epoxied to a mutilated single cylinder motorcycle throttle body. A custom throttle cable retainer was screwed on as an afterthought. The cable was retained with a bolt. The tps only fit by grace of god. How does one begin to untangle this Gordian knot? Ignore it and buy a COTS throttle body.

Further trailblazing, I decided to switch from bicycle brake cable to steel cabling from McMaster Carr. To secure the cable at each end, I machined a custom swageless fitting on the pedal end, and a threaded tube through which the cable is threaded and pinched between two set screws. This ensured the failure mode of the system was slipping of the cable instead of over-centering or breaking the throttle body itself.

Now that the driver could actually control the throttle, we could drill deeper.

Low Hanging Fruit 2: Drivetrain

Reading the feedback we recieved for powertrain over the previous years, one thing stood out: design judges universally hated the way we tensioned our chain drive. Our chain ran from a small sprocket on the output of the motor to a large sprocket mounted to the differential. Our differential mounts were split vertically and bolted together, allowing us to slide shims between the halves to space the sprockets farther apart.

I did, and still do disagree with the design judges. I think a shimmed design is one of the most elegant solutions I have seen for this problem. It weighs the same as a solid design, and less than any design with moving components due to its simplicity. There are no moving components, so reduced points for failure, and none for wear. The compliance was the same as if it were solid, maybe even less if the internal stresses from the bolt clamp load is taken into account. The sims themselves can be of arbitrary thickness, machined ahead of time, and swapped in minutes without dissassembling any system. Although not stated, I still believe the design judges frowned upon our implementation because we didn’t dig into these factors when presenting it, and they viewed it as a cave-man style engineering solution, without the grace of other solutions.

There are a few other solutions to tensioning a drivetrain: an idler gear, a guide, turnbuckles and an eccentric mount. We judged the design space based on the following criteria:

- Serviceability (by number of bolts needed to loosen/tighted to change chain tension)

- Estimated weight (based on other FSAE team designs)

- Bounding box volume

- Compliance/Stiffness (by magnitude of order)

Based on these criteria, the eccentic mount design cam out far ahead. The elegance of the design means that only one or two bolts are needed to change chain tension. The weight and bounding box is greater than comparable other designs, due to it’s inherent size increase, but this is compensated for by the stiffness gained from the size increase.

The eccentric mount is usually retained by friction, either by clamping around the circumference or onto the side, analagous to either a drum brake or a disk brake. Clamping on the side canbe achieved with a bolt through both stationary and moving part of the mount. This bolt also serves as a safety pin to ensure the mount does not spin freely if the clamp load is released under vibration.

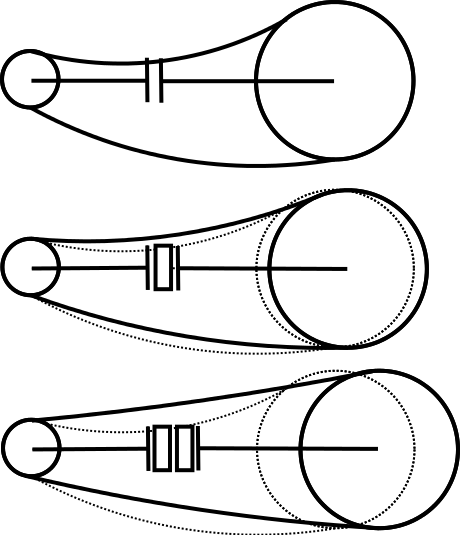

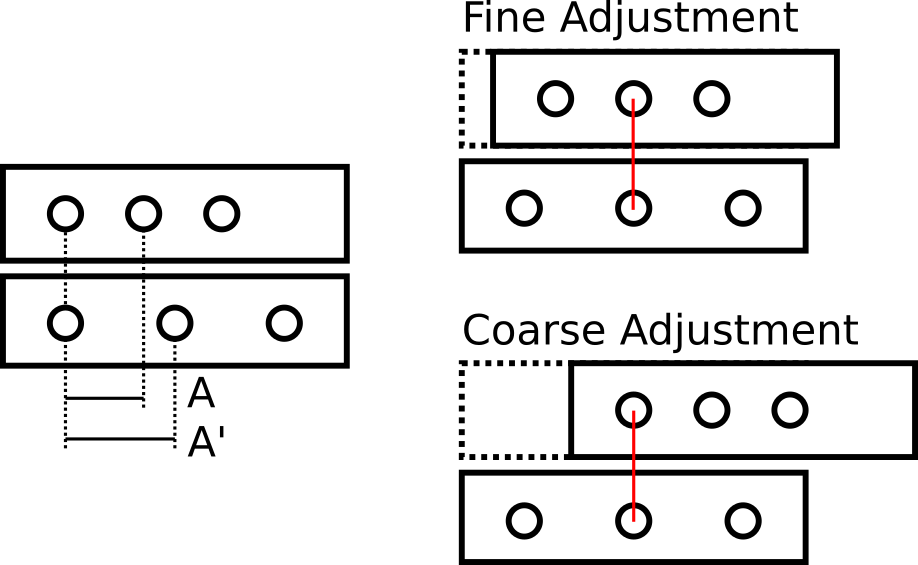

Chain tensioning is never a done deal. The chain will relax and elongated at an unknown rate to an unknown, but somewhat predictable length. Because its job never ends, the tensioner mechanism needs both a broad range for length and fine control within it. Using the horizontal pin mechanism means our team had to get creative with our implementation. A moment of inspiration struck, and I proposed a differential spacing between the pin holes on the inner eccentric ring, and the stationary mount. This was inspired by the measurement action of a vernier caliper. This allowed us to make coarse adjustments by changing pin holes on one mount and not the other, and fine adjustment by moving the pin down to a subsequent pair of holes.

High Hanging Fruit:

The 2018 car had trouble passing the 110 dbc sound requirement in the competition rules. We got around this that year by stuffing the muffler with fiberglass. Packing is very common at the competition, but it critically impacts performance, and we were already having engine reliability concerns. The key aspect of the requirement is that 110 dbc is loud. Extremely loud. There is really no excuse for failing the requirement with a 4 cylinder bike engine. Now that I had my powertrain sea-legs, I felt comfortable taking a critical look at our exhaust design from previous years. The most significant sound dampening device was a Yoshimura Muffler. That made sense to me before I was powertrain lead because it’s a performance aftermarket mod, and we are after performance. However, the Yoshi was only ostensibly a muffler. It made the street bike incredibly loud, illegally so in some states. The stock muffler didn’t. Yes, the stock muffler was incredibly heavy, and poor for power, but we were running restricted and our main power limiting factor was not back-pressure. I went into the 2019 season with the plan to build our own custom muffler, test it, and if it didn’t perform, we would use the stock bike muffler.

I can’t take any credit for the actual engineering design behind the 2019 muffler. I had a minor if not negligible guiding influence on the actual designer, Yuval. My role was to demand rigor in his approach and complete thoroughness in his documentation. He successfully pulled off a data driven design that we took to competition and passed sound without packing the muffler.