Simon's Portfolio

Projects

Capstone Project

In my senior year of college (fall 2018 - Spring 2019) I teamed up with my two good friends and at-the-time captains of the FSAE team to triple dip a single project for the school year. Our goal: A single project that we could submit to our professors as a capstone worthy project, a project requirement for a design class, and as work we could showcase at the FSAE competition in May. The plan: turbocharge our Honda CBR600RR that we used to power the FSAE car.

I will spoil it for you: we had mixed success. Our project was accepted under strict conditions by our senior project advisor and by our design professor. The restriction was that we would have to make distinct contributions to the project for one that could not count as work submitted for the other. We never got a running prototype but I think we cleared significant hurdles along the way.

We were not trailblazing here. Multiple other teams have published extensive papers on successful implementations of this idea. Notably: Cornell and Wisconsin (who turbocharged a single cylinder). We had a few speedbumps to overcome before we could even get started: none of us had a strong foundation on boosted combustion vehicles, none of us had a strong foundation on dyno operating and tuning, we had a non-functional dynamometer to begin with, and our engine was leaking. Despite these small inconveniences, we were unfazed.

Test Stand

The part of the project for our design class required us to revamp the test stand and dynomometer. As powertrain lead of the FSAE team that year, it fell upon me to get our engine in running order and our dyno functional. The engine leak was a gasket issue, of course, but that was only discovered after a complete teardown. The dyno was more troublesome. First I found numerous issues with the aging harness. Then the signal to the computers was being routed through stranded wires plugged into what looked like a 12 cent breadboard. We were starting and running the engine with a battery that would run out of charge frequently. Once I got it running, I learned that if you mis-wire the fuel injectors, the intake will explode, very fun.

Under Construction:

- Water pump

- Oil pump

- Radiator

System Design

The work we submitted for our senior capstone class was the actual system design. This included characterizing the current system, and designing and implementing the turbocharger. In order to assist with our design, we turned to 1-D simulations using Ricardo Wave.

Turbocharger

Since Garret sponsors FSAE teams with a free turbocharger and factory design support, our choice for sourcing was easy.

Simulations

Ricardo Wave is a 1 dimensional engine simulator written primarily in python. It’s analysis focuses primarily on air flow and pressure waves. Because the program is so frequently used in FSAE, there is a stock CBR600RR model included in the software examples that can be tuned to individual teams.

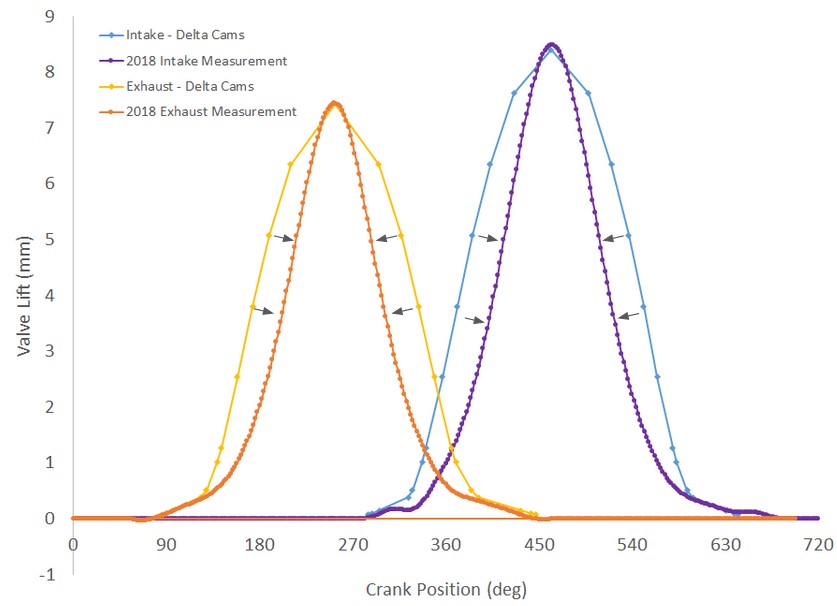

The most impactful tuning parameters are the intake runner lengths and the valve events. On its face, intake runner lengths are easy to measure: pull up the CAD and click “measure”. Unfortunately, the pressure waves in the real engine disagree. The specific geometry of the runners, port geometry, plenum, and the interfaces between them all impact the distance that the dominant pressure wave has to travel. We solved this by starting with the CAD measurement, and then tuning the length parameter in the program until it matched our dyno test curve. Our team had previously had the stock cam profile measured by an outside company, but to ensure accuracy, I measured it myself with a surface plate and an indicator. The most important behavior driving features of the cam profiles are the valve timing events:

-

Intake valve closing

-

Intake valve opening

-

Exhaust valve closing

-

Exhaust valve opening

My measurements for valve timing events aligned perfectly with the measurements we were sent. However, I found the third party company had greatly overestimated our cam’s lobe opening and closing ramp rise.

Also note the finer detail I was able to obtain by measuring in house.

Also note the finer detail I was able to obtain by measuring in house.

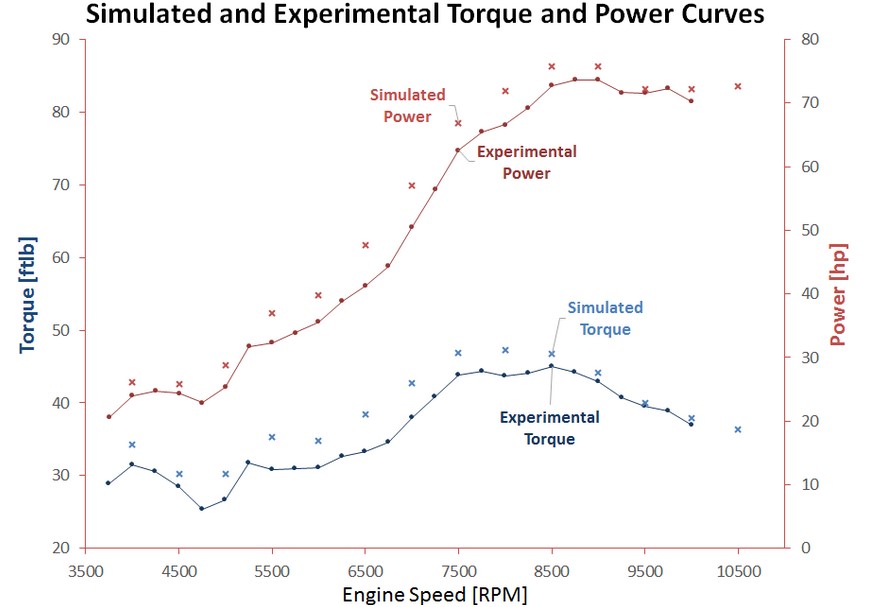

Since all simulations are wrong, but some are useful, we focused on tuning the simulation to reflect the shape of the torque curve. This would enable us to predict the impact of changes to the system on the behavior of the engine.

Twins (1988)

Twins (1988)

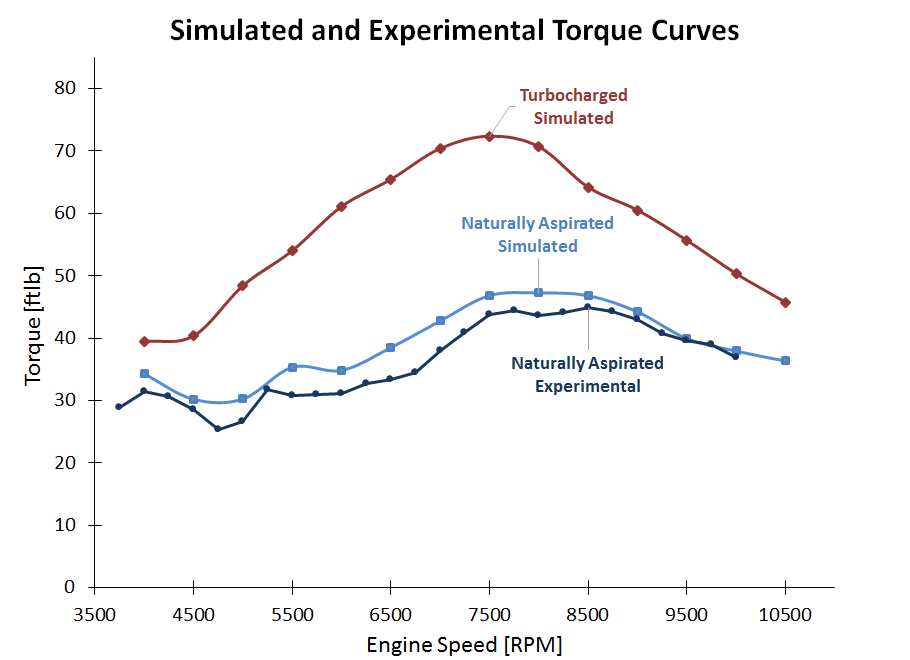

Now we had our simulation dialed in, we could be confident in our predictions of what we would see under boost. I’m not going to go into too much detail on the work that went into choosing the turbocharger and the math that went into integrating it because I didn’t do it, the credit goes to Aris and Stepan. Our simulation showed incredible expected results:

If you’re not scared, you’re not going fast enough

If you’re not scared, you’re not going fast enough

Outline:

- test stand

- system design

- intake

- exhaust

- posters